Horribly compelling: Bruce Conner's nuclear test film still holds us in rapture

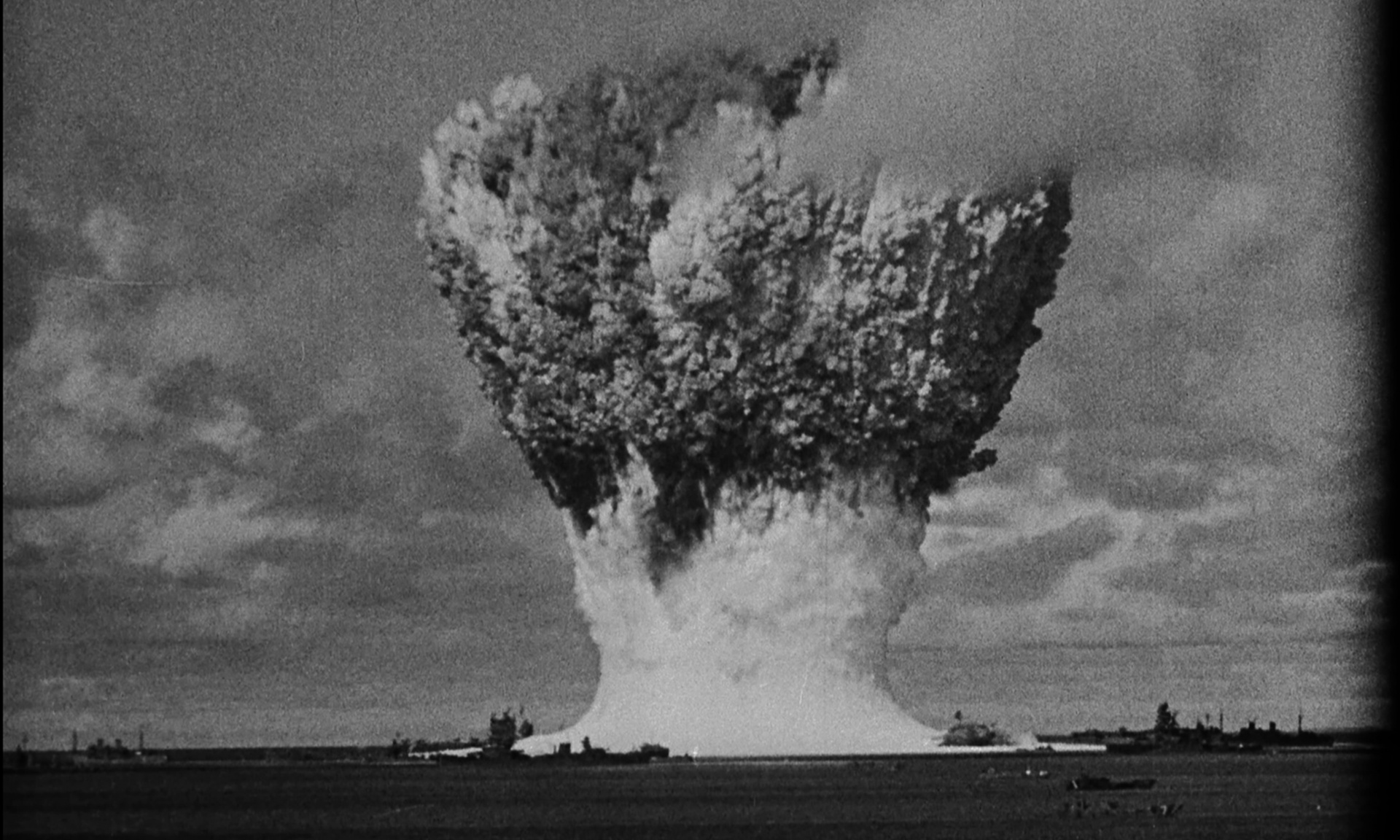

A terrible cloud disturbs the peace of Bikini atoll in Conner’s 1976 film Crossroads. As we watch again and again, we collude in a chilling event despite ourselves.

A beautiful day on the atoll. Water lapping at the beach, ships out on the water. Sea birds screeching, a light breeze mussing the palm in the foreground of a black-and-white view of the lazy Pacific. Then the bomb goes off.

It is 25 July 1946. “Things happened so fast in the next five seconds that few eyewitnesses could afterwards recall the full scope and sequence of the phenomena”, wrote the physicist WA Shurcliff, in the official report of Operation Crossroads, a series of US nuclear bomb tests held less than a year after bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

And then it happens again, and goes on happening, time after time in Bruce Conner’s 1976 film Crossroads, recently restored in high definition and now the sole exhibit at Thomas Dane Gallery, in London.

We see the explosion from cameras mounted behind lead and concrete shielding on a specially constructed tower on the Bikini atoll. We see it from ships and from drone planes, and from high-altitude cameras. We see it filmed with high-speed cameras, developed by the US Department of Defense, that could shoot up to 8,000 frames a second.

The reason observers at the 1946 Baker test at Bikini atoll had so much trouble recalling and describing what they had witnessed, Shurcliff adduced, was the inadequacy of language itself. “The explosion phenomena abounded in absolutely unprecedented inventions in solid geometry … No adequate vocabulary existed,” he wrote. The phrase “inventions in solid geometry” sticks, and sounds less like an event, more like a sculpture. How can one adequately review an atomic explosion?

Dome. Fillet. Side-jets and bright tracks. Cauliflower cloud, fallout, airshock disc, water-shock disc. Base surge, water mound, uprush, aftercloud. The words have a chilling poetry. Shurcliff, who had worked on the development of the atomic bomb for the Manhattan Project and went on, in later years, to be a vocal critic of Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars programme, describes how these terms were arrived at and agreed upon “after two months of verbal groping”, during a conference convened especially to create a terminology. Language has its limits. Words fail, and feel almost entirely inadequate when faced with such enormity.

Conner studied Shurcliff’s report as he planned his film. Watching Crossroads is still a horribly compelling experience. Conner petitioned for the unreleased but declassified footage, some of which had, even just after the explosion, been shown in gung-ho government documentaries about the necessity of atomic tests. They had great propaganda value. The test was broadcast on radio around the world. A kind of awe surrounded the event, which saw the enterprising Parisian engineer Louis Réard give the name of the Marshall Islands atoll to his controversial swimwear invention, the bikini, later that same year.

Footage of the explosion was also used at the end of Stanley Kubrick’s satirical 1964 movie Doctor Strangelove, as Vera Lynn sang We’ll Meet Again, which became perhaps the most redolent song of Britain at war.

The ship from which the bomb had been suspended underwater was completely atomised. No trace of it was ever found, after what has been described as the most photographed event in history. An array of more than 70 ships had been positioned in the atoll around the site of the test. Of these, nine of the biggest aircraft carriers and submarines, some captured from the Japanese forces in the preceding years, sank. Sixty-five others were severely damaged and contaminated. Dozens of pigs, sheep, goats, rats and guinea pigs had been positioned on vessels to study the effects of radioactivity. The pigs – put there because their mass, skin and hair provided an approximate substitute for human beings – died instantly.

In many respects, Crossroads is a found film. “All I added were the splices”, Conner once remarked. Although we witness the explosion 15 times, from different viewpoints and at different speeds (the footage from a high-speed camera extends one second of real time to more than three minutes of screen time), the pace of Crossroads is almost sedate and elegiac.

Presented in two unequal halves, the film allows us to witness the event both as a sudden, wrenching unleashing of power – the association with the male orgasm is unavoidable – and as a slow eclipse of the world. Sometimes, we are lost in the cloud (just as we are lost for words) and in a sublime meteorological event, then we are homing in on huge battleships tossed vertically in the upsurge of a great column of 2m tons of water, rising in an instant over a mile and a half into the sky. The cloud column rose over eight miles above the earth. The scale is hard to grasp.

All this, Conner orchestrates at an almost funereal pace, even though he didn’t tinker with the speeds of the footage itself, only looping the opening sequence, to prolong the wait for the first explosion. As the film progresses, our view becomes more elevated, punctuated by moments where the screen is either totally black or totally white. Even these moments of blankness are dizzying. An image of a cross in a circle appears: the Crossroads of the title, the crosshairs of a telescopic sight, a plus sign, or perhaps even a reference to the crucifixion, as one commentator has noted.

To begin with, the sound seems to be a live recording – sea birds, a white noise akin to the sea, a shock wave and the blast of the explosion itself, aeroplane engines. All produced on a Moog synthesizer by Patrick Gleeson, sound and image are out of sync with the footage itself – and with the judders and swerves of the cameras when the shock waves hit them, sometimes quite long after the visible explosion itself. Gleeson was originally commissioned to collaborate with the composer Terry Riley, but the two eventually worked on music for the film independently. Sound and image sheer together and apart. Riley’s bubbling, repetitive tape-looped and delayed rhythms creep in, and accompany the second part of the film. All we see is an oily, flattened sea with a smudged horizon, a ship silhouetted on the left of the screen, disappearing and reappearing as a radioactive tidal surge overwhelms it, like fog rolling in. I think I see other vague ghost ships beyond.

Every time I have watched Crossroads, since first encountering it at the Berlin Biennale in 2006, I have seen – and remembered – different things. Repeated watching, compounded by memory and mental replay, gives it a cumulative power. You want to watch the explosion. You want to watch the front of the shock wave rush across the water, and the perfect circle of white that expands behind, overtaking it. The fall of the water, the expanding, towering uprush, the fillets, the side jets, the base surge and the fallout are compounded in an awful nuclear sublime, from which it is hard to drag oneself away. You just want to watch it again.

Conner makes us dwell on the incommensurable. Unavoidably, we somehow collude in rapture of the image. He was fascinated by the bomb, using footage from Operation Crossroads several times, both in his first film A Movie (1958), and in the Report (1967), another film using documentary and news footage about the assassination of John F Kennedy. Conner spent most of his career in San Francisco; he argued with Allen Ginsberg over the efficacy of militant anti-Vietnam War protests (believing such solemn events should instead be celebrations, replete with floats and costumes); he worked on underground concert light shows, and went on to advise his friend Dennis Hopper on the filming of Easy Rider. He also made early pop videos, including with the band Devo.

Conner, who died in 2008 at the age of 74, was an assemblagist, a sculptor and photographer as well as a film-maker, and is only now receiving a long-overdue reassessment. Engaging us despite ourselves, Crossroads remains a difficult, unmissable film. You dwell on it, and it dwells in you.